28 March 2023

Feeling Our Way Through Lent – Andrew Cameron

28 March 2023

Feeling Our Way Through Lent – Andrew Cameron

I have been feeling a bit like Jesus lately.

Let me explain. We don’t usually say anything like that out loud, because it sounds astonishingly grandiose. But there are other reasons why we’re not very attuned to ‘feeling like Jesus’.

If we naturally empathise with anyone in the Gospels, it will be the other characters. For example, Matthew 26 includes Peter’s serial denial of Jesus (vv. 57–75). Famously, and tragically, Peter had previously proclaimed: ‘Even if I have to die with you, I will never disown you!’ (v. 35).

From time to time, we might have felt his triumphant swell of rising ego and imagined faux-strength. His later denials occur against that backdrop of pathetic self-deception. While he disowns Christ— ‘I don’t know the man!’ (vv 72, 74)—it is hard not to imagine queasy, shallow, anxious ambivalence roiling his innards. Toward two girls, just because guards and others were near. When the rooster crows, Peter remembers how Christ had seen into him, and weeps bitterly (v. 75). We also sense his utter self-loathing about absolute capitulation, and the bitterness of realizing he knew nothing of strength.

We feel all that because we often feel it. We know inner division, what the ancients called akrasia, our many fears and wants churning our torso and limbs and head. We also get a glimpse of akrasia in Judas’s determination to betray (26:14; what impulse, what pomposity of self-righteousness, drove that?); then, the sunny, false ‘Greetings, Rabbi!’ (v. 49); finally, him seized by a remorse unto death (27:3–5). We’ve been somewhere near those, too.

But, to feel like Jesus? Matthew 26 does give hints of his inner life. ‘My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow’ (v. 38), with the pleas to God that follow.

I wonder, though, what it felt like to say, quite calmly, ‘The Son of Man will be handed over to be crucified’ (v. 2). Or, with some energy, ‘Why are you bothering this woman?’ (as they chunner against her ‘waste’ of something valuable). ‘She has done a beautiful thing to me’ (v. 10). Or straight to Judas (v. 50): ‘Do what you came for, friend.’

Such utterances: imagine from where they spring. The inner resolve. The wholeness of mind with heart and feeling. He has sorrow, to be sure. The pathetic tragedy of those around him calls forth something from his love for them, and for what they could have been. He feels, more than anyone could feel, that break with his Father coming down the pipe. He will take to within Godself the brunt of God’s ‘no’ to the sins of the world. In other words, Jesus has a clarity and love for what and who matter most. These form the wellspring of his, the fullest range, of proper emotions.

But there is no akrasia here. I sense a kind of depth, and connectedness, and purpose, and resolve, and an ability to traverse loss and rejection that we sometimes call ‘courage’, but which is maybe somehow more than even that. I don’t empathise with him, because I am so very rarely like any of that. I don’t ‘feel a bit like Jesus’ because I regularly go to his kind of place. Quite the opposite: I’ve more often been to the place of Peter, and Judas (and maybe even Caiaphas, whose powerful executive resolve actually floats upon a sea of anxiety about the crowds).

Jesus, however, gives himself to humanity as human, in part that we may get a glimpse, a sense, even a feeling, of how properly to be human. People sometimes bridle at that thought. After all, if he was God, maybe he was a super-being unlike us. Or, his sinlessness means we never get to compare with him. I think those reactions miss the brilliance of the Incarnation, where the Second Person of the Trinity is also the human person, Jesus of Nazareth. That’s it. We’re invited to connect with his way of truly being human, so that incredibly, we can ‘participate in the divine nature’ (2 Peter 1:4).

The Passion, of course, primarily brings relief: that every, single sin borne of fear and ambivalence and self-deception, can receive the mercy of God’s forgiveness, thanks to Christ’s atoning death, and his superb Resurrection. When you meet St Peter, ask him what it was like to be restored and forgiven a few days after the worst day of his life.

But in this season of Lent, and as you read and hear of his Passion, try something else. Try to imagine what it might have felt like to be the man who moved through it as Jesus did—who could say, and do, and be, such as Jesus was. Imagine what it felt like to be him, in each utterance, interaction, and step toward the Cross.

You will love him more. You may even shift a little, within yourself, just a bit.

Andrew Cameron

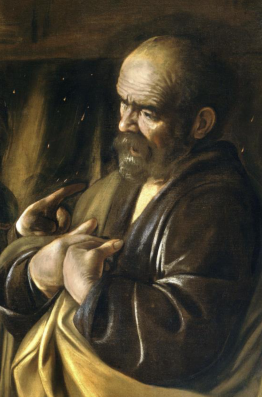

Picture: The Denial of Saint Peter by Caravaggio, 1610. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City